Category Archives: 01. General Information

Special fuel filler position Turner 950 Sports

Introduction

The standard position for the fuel filler for the Turner 950 Sports Mk1 is inside the boot (trunk). The standard Austin A35 fuel tank has been slightly modified, changing the angle of filler pipe in the direction of the centre of the car to have better access to the filler cap with the boot lid open. The risk of spilling some petrol inside the boot is of course present. But another disadvantage was more important for Turners used in racing especially when entering a long distance event (like a Six-hour race): it takes too much time to open the boot lid!

208JJH at Brands Hatch in October 1960

208JJH at Brands Hatch in October 1960

My Alexander-Turner 950 Mk1 (60-307) therefore had the filler opening repositioned to the outside of the car, just to the right of the boot lid. This has (apparently) been done in the Alexander work shop as this car had the modification from the beginning (March 1960). The above photo taken at Brands Hatch (October 16, 1960) clearly shows that the petrol filler has been moved.

Rear body of 60-307 with original position of external fuel filler still visible

Rear body of 60-307 with original position of external fuel filler still visible

During the restoration of 208JJH I noticed that there used to be a hole in this area that had been closed again with GRP and I thought this could have been a later modification that had been dropped again. On basis of the above photo it is clear that this was the original hole and I recently decided that the car should receive the (original) fuel filler position again.

Modification

The standard pipe connection and hose have a 2¼“ (57 mm) diameter. For the modification we require either a very flexible 2¼“ fuel hose or some pieces of metal pipe of the same diameter bended 45⁰, and some pieces of 2¼“ rubber hose to connect these pipes. Because the standard filler pipe has 30⁰ angle in the opposite direction of where the new filler opening will be positioned, some sharp bends will have to be made in order to have the filler pipe and filler cap positioned in an angle perpendicular to the sloping body at the right side of the boot lid.

New filler pipe construction

New filler pipe construction

The photo shows the construction of the filler pipe as described, using the original 2¼“ filler cap construction. Found a grommet with an inner diameter of 2¼“ (57mm) suitable for a panel hole of 2¾”or 70mm (grommet for a VW T25 bus used from May 1979 till July 1983). It fitted beautifully in the 70mm hole drilled in the GRP panel.

Final result; compare with original photo.

Final result; compare with original photo.

The end result is very pleasing and fully in line with the original photo from 1960.

First season Alexander-Turner 208 JJH

First season Ken MacKenzies Alexander-Turner

The typical atmosphere of club racing in the 50’s and 60’s is regarded as pure nostalgia by many of us nowadays. The following article describes the scene, following Wing Commander Ken Mackenzie through the 1960 season, participating with an Alexander-Turner 950 in the Autosport Series Production Sports Car Championship Class A.

It was the very early morning of Easter Monday 18 April 1960 when the transporter, so kindly provided by Alexander Engineering of Haddenham, left Northwood on its way for the 100 mile journey to Mallory Park. Quite an improvement over the “hotted-up“ Volkswagen Beetle, the driver’s daily transportation, that until then had to do the job. This was the day: the beginning of another season in the Autosport Series Production Sports Car Championship for Ken Mackenzie.

Wing Commander K.W. Mackenzie had quite a background in racing by now. Whilst in the RAF Reserve in 1939 he started building, modifying and rallying various cars. After the war he started racing in 1956 with various cars, including RWG and an Elva Climax. In 1958 he was fairly successful in a (works supported) MGA gaining first place in the 1600 cc Class in the Autosport Championship and doing even better with the (Alexander suported) Austin Healey Sprite (Registration Number 6 TMT) during the 1959 season (gaining 20 places during the season), teaming up with (Squadron Leader) Paddy Gaston and Chris Tooley and winning the Championship.

It was only a few weeks before that Mackenzie had taken delivery of the brand-new Turner 950 Sports, built and assembled by Turner of Wolverhampton on their premises at Pendeford Airport. Confronted with the convincing results of Turners in the 1959 season (Bob Gerard becoming overall winner, Austin Nurse and B. Gilbert gaining several successes) Ken Mackenzie decided to change over in 1960 to the successful creation from Turner Sports Cars. But Ken Mackenzie wanted more – he wanted a winner.

Late 1959 Turner announced the arrival of its redesigned 950 Sports model with a new full-width grille, curved windscreen and smoothened rear. At the same time, Michael Christie, MD of Alexander Engineering informed the press that they would become the new distributor of Turner Sports Cars for Southern England. Mackenzie decided that Alexander should tune the standard Turner, not only because they delivered the car, but also because of the longstanding relationship between Mackenzie and Fred Hillier, Alexander’s “Chief Mechanic”. Fred Hillier was a Senior NCO Instructor at the RAF Apprentice School at Halton and he had prepared and driven the “Schools” Tojero with Climax FWA engine for several years before joining Alexander Engineering after his retirement from the RAF.

Mackenzie made a deal with Michael Christie to race an Alexander-Turner for the 1960 season, the chassis and (BMC-A) engine of which would be prepared by Fred Hillier and the chaps from Alexander after delivery by Turner. The car, a Turner 950 Sports registered 208 JJH on 21 March 1960 in Hertford, had to fulfil the Appendix J regulations, which is why the famous Alexander light alloy cross-flow cylinder head could not be used, much to the disappointment of “businessman” Michael Christie.

The entry list for Class A (up to 1000cc) in 1960 showed sixteen names of which five drove an Austin-Healey Sprite, nine went this year for the fashionable Turner 950 Sports, with one Berkeley B 105 and one Fairthorpe Electron. Well-known names like J.H. (Paddy) Gaston in a special-bodied Sprite and F.R. (Bob) Gerard in a Turner 950 were mixed with drivers whose names only a few enthusiasts nowadays can remember. As can be seen from the entry list, the engine most commonly used was the BMC-A 948 cc in various forms of tuning. Most of them were bored out (+ 0.060″ or more) to increase the capacity to a value just within the 1000cc class. The exceptions were the air-cooled 2-cylinder 692 cc Royal Enfield in the Berkeley and the 948 Standard-Triumph engine (Alexander-tuned, by the way) in the Fairthorpe. Remarkably, there were no Ford engines used at all in this class, though in a few years’ time this would be the engine to beat. But this season, as in the previous years, it would be a “close racing” battle again between Sprites and Turners, having the same engine though a totally different chassis lay-out.

We have to note that there were actually two races on Easter Monday: next to the one in Mallory Park organised by the Nottingham Sports Car Club, there was the one organised by the British Racing and Sports Car Club at Brands Hatch. The latter had a “fatal attraction” at Paddy Gaston with his Sprite deciding to join this race instead of Mallory Park. Paddy (who had made a living out of racing, modifying engines and selling tuning parts from his premises at Richmond Road, Kingston-upon-Thames) was rather unhappy in his first outing, rolling his Sprite on the eighth lap, badly damaging the car but escaping himself with only some bruises. Paddy Gaston, the previous year’s team-mate of Ken Mackenzie, would become Ken’s biggest rival this year, in spite of his unhappy start and his missing the following race.

So different was the season’s start for Ken Mackenzie! On the 1.35-mile-long Mallory Park circuit, car and driver seemed to be unbeatable that Easter Monday. The preparation by Alexander was immaculate and Ken, in spite of the early rise, showed his skills in beating all the other Turners. It was pure delight: winning 208 JJH’s maiden race goes against all general belief that a car has to be developed over a couple of races before being able to compete effectively. It turned out to be a true Turner race, with Turners finishing in the first five places. Was this the way the season would turn for Ken Mackenzie and his Turner?

No, definitely not. The second race of the season was organised by the Maidstone and Mid-Kent Motor Club on Saturday 30 April at Silverstone. Again, at the beginning of the 20-lap race it looked as if nothing could beat Ken Mackenzie and his Alexander-Turner, leading the pack of Sprites and Turners. But then, on the fourth lap, he had to quit the race because of a broken weld in the throttle pedal! Delight and misfortune are so very close in racing, as Mackenzie experienced once more. The race was won instead by “good old” Bob Gerard, leading five other Turners. The Championship placing after two races were headed by Simon Scrimgeour, being the steadiest in finishing.

May 8, 1960 Mallory Park

May 8, 1960 Mallory Park

Mallory Park, the third race on 8 May saw the return of Paddy Gaston, only 3 weeks after his accident at Brands Hatch. The dominance of Turners had gone with Paddy Gaston in his Sprite leading the field from start to finish in spite of whatever Ken Mackenzie and Bob Gerard tried to do with Mackenzie ending 2nd in Class. It must have been an extremely well-prepared car and a skilled driver to beat the Turners, since all the other Sprites ended far back in the field.

The fourth round brought Mackenzie and friends to Snetterton, the 2.7-mile-long circuit in Norfolk. Again it was Paddy Gaston who dominated the race, with the Turners battling between themselves for second place. David Pritchard even applies the term “splendid duel” covering that part of the race for Autosport. Behind Gaston, it was Bob Gerard again taking second place. For Mackenzie life was hard; half-way through the race he had to give up with no clear cause mentioned. So far, two finishes and two mishaps for Mackenzie, losing points in the Championship on the others.

Martini 100 at May 21, 1960

Martini 100 at May 21, 1960

Although not part of the Autosport Championship, Ken Mackenzie took part in the Martini 100 races on May 21st at Silverstone. And he did well, finishing second in Class right behind Jan van Niekerk in his GSM Delta.

On Whit Monday, 6 June, two races (both qualifying for the Championship) had been organised with the result that in both races only a few participants in the A Class showed up, not contributing to the overall excitement of the spectators. At Mallory Park only five Class A cars started in a race that was won by George Morgan in his Turner, in fact beating three other Turners. Ken Mackenzie decided to head for Goodwood (probably because Gaston went there and it was somewhat closer to his home in Northwood) where the B.A.R.C. had organised a 20-lap race on the 2.4-mile-long circuit. Because there were so few Championship participants, the organisers had allowed others to join the race as well, meaning that even a Jaguar Mk II saloon was regarded a Sports Car that day. It still turned out to be a crazy fight with the cars of Mackenzie and Marriot touching each other in Woodcote Corner. It did not help because Gaston finished first, well ahead of the others in Class A, with Mackenzie taking fourth place.

Next came Snetterton: on June 19th Mackenzie achieved 3rd place overall and 2nd in class with a fastest lap time of 2:04,0 and an average speed of almost 80 mph but beaten by Bill Moss in a Marcos GT (a.k.a. the ‘Ugly Duckling’) and Robin Bryant in another Turner.

As the next race would only be at the end of July, Mackenzie decided that there was plenty of time to take his Alexander-Turner “overseas”. Dunboyne, County Meath, Ireland, was the setting for an annual race weekend, this year sponsored by “Messrs. Martell & Co., Cognac”, a contest in which Mackenzie had taken part before with cars such as the MG A. The Leinster-Martell meeting of Saturday July 9 actually consisted of two events, the Holmpatrick Trophy Race and the Leinster Trophy Race, where the organising committee would decide in which race a car would participate, simply on basis of their opinion as to whether a particular car could lap the Dunboyne Circuit at 75 mph average speed! The Alexander-Turner therefore would take part in the Holmpatrick Trophy Race. Saturday 2.55 p.m. saw the start of this 15-lap, 60-mile race. Many competitors had used the opportunity to practise on the Thursday and Friday night before. Not so for Mackenzie who consequently had to fight his way through the entire field after the start. The field consisted of a mixed bag of all kind of different cars and engines capacities, like Austin Healey Sprite, MG TD, TR 3 and even a Fiat Special. It would become a very exiting race between W.D. Lacy in a TR 3 and Ken Mackenzie in the Alexander-Turner. One would think that this could hardly be called a fair competition, but amazingly the small Turner (998 cc) was a real threat for the bigger TR (1991 cc). Until on the 10th lap fate struck and Mackenzie had to withdraw with “mechanical trouble” and Bill Lacy could finish the race without any problem.

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](http://www.bobine.nl/turner/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/clip_image0026_thumb.jpg) Mackenzie battling at Dunboyne, Ireland

Mackenzie battling at Dunboyne, Ireland

Mackenzie himself reports twice on this event. In a letter to Autosport of August 1960 he writes: “The facts are that on the 10th lap, when leading Lacey, the eventual winner, and lapping at over 80, my radiator was holed and I lost all the water and retired with a resultant cracked cylinder head. In fairness to the car, which was the only other entrant in this race besides the eventual winner to lap at over 80, I would like this to be put across.

In another letter of October 1985 to Motorsport Mackenzie looks back: “This car was very successful in the Autosport Trophy, National and some International events, only not being placed in two out of 16 races and these due to minor mechanical problems. The worst being the Irish Holmpatrick Trophy, lost four laps from the end by a holed radiator, the Turner being timed at 108 down at the back straight, the second losing an Autosport trophy class win by a broken throttle linkage at Silverstone”

About the 8th race of the season we can be rather short as it was cancelled. On 31 July at Mallory Park there were too few entries from Classes A and C, even if they were combined in one race. Nevertheless we have to mention this race as it saw the first performance of another famous Turner, the Pat Fergusson-driven Turner-Climax, better known as “Tatty” Turner. This car, built by Allen Smith who also tuned the 1216 cc Coventry Climax FWE engine, was not yet homologated and just took part as a try-out in the Class B race. Fergusson would gain great successes in 1961 with this car as did Warwick Banks in 1962; both men won the Autosport Championship in their classes.

Ken Mackenzie still had every possibility to win the 1960 Championship himself with, after eight races, a second place in Class A with 23 points, just behind Paddy Gaston leading his class with 28 points. With (officially) one more qualifying race and the “grand finale” to go, it was becoming exciting in Class A. Managing Editor of Autosport, Gregor Grant, was of the opinion that participants of Class A and C should have an equal chance (as Class B) to win the overall Championship and therefore tried to arrange an extra race to replace the cancelled one of August 31.

Snetterton om August 6th was the venue of the ninth race and a very special race it was! Combined with the last qualifying race for the Autosport Series Production Sports Cars Championship, Saturday August 6th saw the final of the 1960 Autosport World Cup for GT cars between the teams of Holland and Great Britain. The Class B race took place together with heat 1 and Classes A and B with heat 2 of this GT final. David Pritchard was full of praise for what he saw that afternoon: “Superb Snetterton” was the ringing title of his first-class story in Autosport.

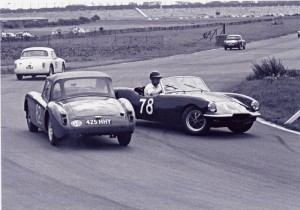

Left: Ken Mackenzie at Snetterten;. Right: Mackenzie leading Bob Gerard in his Turner JU 5

Left: Ken Mackenzie at Snetterten;. Right: Mackenzie leading Bob Gerard in his Turner JU 5

The second heat saw an interesting battle between such cars as the Porsche S90, the Lotus Elite and the MGA Twin Cam, remarkably closely followed by Paddy Gaston in his special-bodied Sprite. That Gaston finished fifth overall in this race indicated once more the excellent qualities of car and driver. Ken Mackenzie did quite well that afternoon, finishing third in class behind Gaston and Gerard, nevertheless losing 4 points on Paddy Gaston who now led the Championship ranking with a safe 9-point lead, with Ken Mackenzie and Bob Gerard in equal second place.

Mackenzie ahead of the rest at Aintree August 7, 1960

Mackenzie ahead of the rest at Aintree August 7, 1960

Managing Editor of Autosport, Gregor Grant, managed indeed to organise an additional race for Class A to make up for the missed opportunity of earning Championship points on July 31. Just a day later, August 7, during the BARC meeting at Aintree, the 3-mile-long racing circuit near Liverpool, the rivals in Class A met again. The fact that Paddy Gaston could not participate due to mechanical troubles that came to light just before the race was a tremendous opportunity for Mackenzie (as well as for Gerard, of course) to get closer in points. During the first race of the day it was the usual “battle of the Turners” with George Morgan leading in front of a MGA Twin Cam and the other Turners, including Mackenzie who finished fourth in class and (worst of all) behind Bob Gerard who now took over second place in the Championship. One could say without exaggeration that there was a real “Turner” dominance that afternoon in Aintree; since Gaston did not start, the Turners had no problem in taking the first four places in Class A, only then followed by a Sprite and a Fairthorpe Electron.

![clip_image002[8] clip_image002[8]](http://www.bobine.nl/turner/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/clip_image0028_thumb.jpg) The Three Hours of Snetterton preview

The Three Hours of Snetterton preview

Since Mackenzie’s race was so early in the day, he found there was plenty of time for another race later in the day. In a Sports Car race for up to 1000 cc overhead valves and up to 1200 cc side valve engines (note the creativity of organising committees in forming competitive classes) Ken managed to finish third overall behind a DRW Ford and a Lotus 7 with Austin engine, outperforming a TR2 and 3, as well as a Twin Cam MGA.

The “Three Hours” of Snetterton formed for the fourth successive year the final of the Autosport Series Production Sports Car Championship. This unique racing event (part day and part night; the only one in the UK) holds a very special place in the heart of many a driver. The ambience is reminiscent of Le Mans: the excitement, the crowds, the headlamps peering through the darkness, the refuelling, even the start itself has that “nostalgic” atmosphere of racing at its best. And besides that, a wealth of points could be gained (double points during this final) meaning that everything is still open.

In the preceding weeks, Autosport had presented the list of final participants and contemplated the chances of the various rivals. A full-page picture gallery of the drivers still in the race for Championship gave an extra dimension to the upcoming event. Among the ones pictured was Ken Mackenzie, who regarded this as a tremendous reward for a beautiful season, no matter what the final “Three Hours” would bring. A reward for skill and perseverance of the driver and, most of all, for the quality of the Alexander-Turner and those that had prepared the car.

On many occasion, before and after, Ken Mackenzie expressed his admiration and respect for that “little” car; “in fairness to the car”, as he once said.

“Those of us who raced Turners, of whatever mark or power, enjoyed some classic sport, safe, reliable and competitive,” were his words when he looked back in Motorsport 15 years later.

What should have been the “culmination of the season” was in fact utterly disappointing for Mackenzie. The “Three Hours” of Snetterton started at 5.30 p.m. precisely and for almost 2 hours things looked so good for the Alexander-Turner. Then, at 7.15 p.m. Ken had to retire after 50 laps because of an “almost total absence of gears”. Mechanical failure meant that the end of the season had come, prematurely but inevitably.

![clip_image002[10] clip_image002[10]](http://www.bobine.nl/turner/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/clip_image00210_thumb.jpg) Turner add referring to racing successes at end of 1960 season

Turner add referring to racing successes at end of 1960 season

The 1960 Championship Table shows Ken Mackenzie in tenth position, the overall Championship being won by Chris Summers in a Lotus Elite, competing in Class B. Since Paddy Gaston (AH Sprite) and George Morgan (Turner) qualified with their second and fourth place overall for a special Championship Award, Ken Mackenzie moved up in Class A to third place behind Bryant (Turner) and Gerard (Turner) to gain a Trophy to remember this fine season for ever.

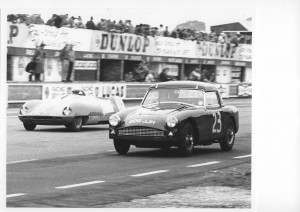

Brands Hatch October 16 1960

Brands Hatch October 16 1960

To close-off the season Ken participated on October 16th in another race at the 1,24 mile long Brands Hatch circuit, in which he ended 1st in class with a fastest lap 1:07,4 or 67 mph: a worthy closure of his first season in the Alexander-Turner!

BK

Turner-Alexander or Alexander-Turner?

Turner-Alexander or Alexander-Turner?

It had become a kind of tradition for Alexander Engineering of Haddenham (Buckinghamshire) to present their latest developments in the form of a special testday, giving the press ample opportunity to judge the qualities of the various cars that were put at their disposal. The company, headed by Michael Christie, had built up quite a reputation in making engine and suspension conversions for practically every available car in the late fifties and early sixties. In particular, their achievements in upgrading the BMC-A engine, found in so many cars in that period, established their name among the long list of tuning companies like Derringtons, Raymond Mays, Aquaplane, Arden, Speedwell and Downton, to name but a few.

It was a surprise for the motoring press when Michael Christie announced in November 1959, during their yearly autumn presentation, organised this time in the Weston Manor Hotel in Bicester, that Alexander had made an agreement with Turner of Wolverhampton and would distribute the new Turner 950 Sports (later to be known as the Mark 1). Delivery of the new car would commence after Christmas and many products from the vast Alexander range, including engine, suspension, brakes and interior, would be available for the Turner-Alexander right from the start.

It is interesting to note that Alexander went their own way with respect to component sourcing. Apart from the obvious choice of their light alloy cross-flow cylinder head, the long list of “Approved optional equipment” offered no less than 20 different items, amongst which a Lockheed servo in combination with the Girling disc-brake system, specially developed for the Healey factory (Sebring) Sprites and the Turner 950 Sports.

The cross-flow cylinder head (CR 9.4 to 1) delivered in combination with twin SU H2 carburettors about 60 bhp at 6000 rpm, compared to the 43 bhp at 5000 rpm (CR 8.3 to 1 and twin SU H1) of the Turner in standard form. The Autocar, reporting about the new Turner-Alexander on 4th December 1959, mentioned that a maximum output of 80 bhp was claimed if combined with high compression pistons and a road-racing camshaft. They also mentioned that a new company (Alexander Autos & Marine Limited) would market the car, using conversion parts supplied by Alexander Engineering.

In the January 1960 issue, Motor Sport complimented the car they tested during the November presentation in Bicester. Especially the body finish and weather protection impressed them. Funnily enough the engine of the Alexander-Turner (note the different order of the two brands as compared to the Autocar story) was less impressive, being described as “a rather tired hack engine which did not help to show the car up in a good light”. However, they promised to perform one of their “normal rigorous tests” on the car in the following months, a promise they did not keep.

Two road tests, however, were published as a result of the active marketing policy of Alexander. The first one was in Sports Car and Lotus Owner in March 1960, followed by another in The Motor of August 10 of the same year: quite some coverage for such a small company.

David Phipps (Sports Car and Lotus Owner) is full of compliments, referring to the Alexander-Turner (333 KPP) as “a 948 cc car with the performance of the 1½-litre MGA”. Performance and roadholding are described as “very good”. The Alexander-Turner, of course, had much in common with the Turner 950 Sports, but Alexander offered the double trailing arms to locate the rear axle as a standard, a construction that Turner recommended for the more powerful tuned versions and the Turner-Climax Sports with the Coventry Climax FWA engine. The standard 15 inch wheels were combined with a somewhat lower geared final drive (4.875 compared to 4.55 for the standard Turner). Acceleration figures were impressive for a 950 cc car: 0 – 60 mph in 13.6 seconds; and the recorded top speed was over 90 mph! David Phipps reported that Alexander had started experimenting with 13 inch wheels to further improve road handling.

Another interesting observation is that Alexander were apparently still experimenting with the inlet manifold, showing a large balance pipe between the four inlet tubes (yes four, no Siamese port on the cross-flow Alexander head!) in March 1960, that had been reduced to a thin balance pipe by mid-1960 in its final form..

The Alexander-Turner tested by The Motor (500 NKX) had received the thirteen inch wheels as already indicated in March. Other changes included twin SU H4 and the final drive back to 4.55. The acceleration from 0 to 60 mph remained unchanged at 13.6 sec, while maximum speed went up to over 95 mph! The Motor Road Test No. 28/60 is very accurate in this respect, even down to the 5% misreading of the speedometer. The Motor came to the conclusion that this car was perhaps too highly tuned for the majority of sports car buyers, but what remained was a feeling of “enjoyment of a comfortable, lively and exceptionally controllable little car”.

Although Turner’s are often referred to as “kit cars”, in fact only a part of the total factory output was supplied as a kit, especially for the home-market. A considerable part of the production went overseas and these were all completely assembled in Wolverhampton. Alexander delivered their “kit” on request, adding all the Alexander “goodies” the customer had asked for, but also undertook the conversion and tuning of factory-built Turners.

In the Sporting Motorist of January 1961, proud owner Ashley Clarke describes in detail how he built an Alexander-Turner, supplied as a kit, in just a hundred hours. It offers an excellent insight into what building a Turner meant: trying to save Purchase Tax (which had been lowered in April 1959 from 60 to 50% of the basic price, still equalling between £250 and £350 in the case of the Turner 950 or Turner Climax) meant investing a lot of spare time.

Alexander remained official Turner distributor till the mid-sixties. Turner had a habit of changing agents rather frequently (or was it the other way round?). In the period from 1955 to the end of the decade, Bob Gerard, combining racing and selling Turner Sports Cars, was their East Midlands Distributor, while Field’s Garage in Chichester had taken responsibility for South East England. In the early sixties, apart from Alexander Autos and Marine Ltd. covering the South, Gordon Unsworth of Motorway Sales in Derby became Turner’s new agent, taking over from Bob Gerard.

Up to 1964, things looked rather bright for Turner, still with amazing racing success, Turner’s keeping lap records at every UK circuit and with exports across the Atlantic and to South Africa continuing to be their main source of income. But Jack Turner went into voluntary liquidation in early 1966 following Jack’s illness and a number of other mishaps.

Alexander Engineering Co. Ltd. still exists almost forty years later at the time of writing. Now headed by son Timothy Christie, they are an active as well as important supplier to the automotive industry, in particular in the area of accessories and lighting equipment. They still occupy their historic premises at Thame Road in Haddenham.

BK 1999

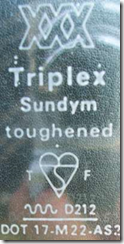

Triplex Glass Manufacturing Date Codes

Triplex Glass Date Codes (prior to Jan 1969)

Cars made in the 1950’s to the late 1970’s can be dated by the ‘TRIPLEX CODE’ etched into the toughened glass. Note that it dates the GLASS, so is only an indication of the cars age, assuming the glass is original.

Year code

The year code can be found in the Nine letters make the word TOUGHENED. One dot below a letter gives the year of the decade:

T O U G H E N E D

- T = 1

- O = 2

- U = 3

- G = 4

- H = 5

- E = 6

- N = 7

- E = 8

- D = 9

- No dot = 0 (or possibly a dot under a space after the last letter)

This code also works if you have a TRIPLEX curved windscreen with the (also Nine letter) word LAMINATED instead of TOUGHENED.

Quarter code

To further determine the approximate month of production, just look for two dots in the TRIPLEX logo on the glass.

T R I P L E X

One dot above T, R, E, or X gives the quarter of the year the glass was manufactured:

- T = Jan, Feb, March,

- R = April, May, June,

- E = July Aug, Sept,

- X = Oct, Nov, Dec.

Example: say your car is from the 50’s, then TRIPLEX TOUGHENED, with one dot over the ‘R’ in Triplex, and the other under the last ‘E’ in Toughened, indicates ‘April/May/June 1958’

Date code 2nd quarter 1959 Older example from the 30’s.

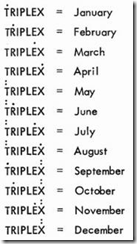

Triplex branded Glass (after Jan 1969)

The year indication is still identical to the TOUGHENED or LAMINATED system, but the month code changed. The month of manufacture is now indicated by the dots over the word TRIPLEX:

August 75 Later logo with unknown Date Code system

History of UK Glass Manufacturers for the Automotive Industry .

British Indestructo Glass Ltd (to be investigated)

Pilkington (now owned by Nippon Sheet Glass Co., Ltd).

In 1929 Pilkington and Triplex formed a joint company to build a works at Eccleston, St. Helens. Pilkington gradually increased its shareholding in Triplex until by 1965 it became the majority shareholder.

In Pilkington’s Queenborough factory on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent the original glass products were made under various brand names like Triplex, Sigla, Bilglas or SIV. Today they can still supply products with the original trademark. The Queenborough factory has made classic windscreens for the aftermarket since the late 1950s, and still retains the vast majority of the tooling produced ’’in-house’’. The range consists of over 2000 parts including, AC Ace, 1953/63, Mercedes 220 1961/71, Aston Martin DB 4 1958/65 and MG’s to name a few. The specialist factory is certified according to BS EN ISO 9001: 2000 ensuring that all legal requirements are met.

Triplex Safety Glass Co. Ltd. (Est. 1922).

Hythe Road, Willesden, London, N.W.10. “TripleX” laminated and toughened safety glass, both plate and sheet, Multi-ply and bullet-proof glass, Curved safety glass, Shaping, forming and manipulation of “Perspex” and other thermoplastic materials. Trade names: TripleX, Triplite, TriFlex.

Tudor Safety Glass advertisement, 1956.

Tudor Safety Glass advertisement, 1956.

Tudor Safety Glass Co. Ltd. (Estd. 1935).

Spring Place, Kentish Town, London, N.W.5. Two toughening, ten bending furnaces: electricity, gas. Laminated and toughened safety glass, machinery glassware. Trade name: Vinylex. Tudor has been taken over by Triplex Safety Glass some decades ago and thus belongs to the Pilkington Group of companies.

![clip_image002[4] clip_image002[4]](http://www.bobine.nl/turner/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/clip_image0024_thumb.jpg)